The following public talk was delivered on 7 September 2013, at the le Carré’s People symposium, at Birkbeck, University of London, co-organised by Penguin Modern Classics, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

N.b. This is the original text, with minor additions in square-brackets from my vantage point a decade on in 2023.

On 8 February 1966, David Cornwell, aka. John le Carré, was interviewed by broadcaster Malcolm Muggeridge for BBC-2’s talk show Intimations (1965-66) – which, the previous year, had featured popular literary novelists Lawrence Durrell and Robert Graves. In this TV appearance, the 34 year-old writer names Graham Greene as a major influence on his writing, along with Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes (1911) and The Secret Agent (1907). Le Carré launches a withering attack on James Bond, seeing him as an “international gangster”, symbolic of a culture where consumer goods are overvalued. In contrast, he outlines his own concerns with ethics and verisimilitude; his work, he claims, represents “the moral search of the solitary”. Le Carré, perhaps tellingly, refers in jaded tones to becoming embroiled in the “circus” of Public Relations. He also claims not to be attracted to film as a medium and that he would prefer to adapt the work of others, following his experience co-scripting The Spy Who Came In From The Cold (1965 film). He does not mention prospective television adaptations of his work, or the prospect of original writing for television.

As Randall Stevenson has stated, ‘television […] opened up new forms of cultural engagement for the population as a whole’.[1] From the 1960s, TV was deeply involved in social questions; for example, David Frost’s forceful inquisitions and drama that was instilled with a topical and ethical spirit by the Canadian Sydney Newman. Newman had worked for the National Film Board of Canada from 1941, and was promoted within the organisation by Scottish filmmaker John Grierson during WW2; Grierson later assisted with Newman’s move into television production in 1949. Grierson had coined the term ‘documentary’ in 1927 and produced films of social conscience and poetry like Housing Problems (1935) and Night Mail (1936). He saw an ethical imperative – ‘I look on cinema as a pulpit and use it as a propagandist’ – and John Caughie has compared him with Lord John Reith, founder Director-General of the BBC.[2] Newman was more comfortable with commercial values than Reith, but he did not neglect the legacy of the secular Scottish radical Grierson.

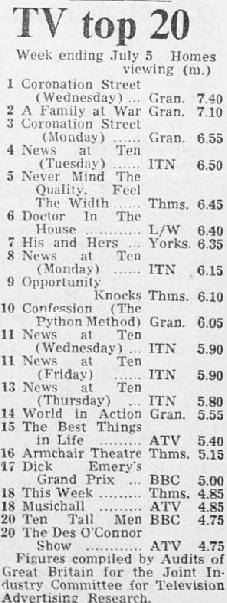

Newman moved to the BBC in 1962; as Head of Drama he split the department into three distinct areas of production: serials, series and single-plays. Serials included adaptations of literary works; series tended to be economical and long-running, gaining large audiences through the familiarity of regular casts and narratives that fused the everyday with the melodramatic – though they were not necessarily lacking in social comment. See Tony Warren’s Coronation Street (Granada for ITV/ITV1, 1960- ) and Troy Kennedy Martin’s Z-Cars (BBC TV/BBC1, 1962-78).

Single-plays tended to be the most experimental type of drama on television. ABC’s Newman-led Armchair Theatre had pioneered in naturalistic television drama with plays like Alun Owen’s Lena, O My Lena (1960) and, the same year, 14 million viewers had tuned into its Harold Pinter play, A Night Out. On the BBC, Newman co-initiated The Wednesday Play in 1964, which featured socially engaged plays like Up the Junction (1965) and Cathy Come Home. These subsequently much-repeated dramas gained 9.21 million and 11.8 million viewers on their first screenings, respectively, [according to BBC data].

Cultural historian Robert Hewison has described how the 1950s and 60s saw challenges to the Leavisite privileging of a literary and artistic canon. Pop Art and the vastly popular music of the Beatles and others were being taken increasingly seriously, which marked a logical advance from how the Kingsley Amis generation had elevated jazz, detective stories and science fiction. The Robbins Report of 1963 had led to an expansion of University education; culture was being redefined, outside the control of Oxbridge-educated ‘mandarins’. In literary terms, the Powell and Waugh generation was supplanted by that of Larkin and Sillitoe. Cultural Studies was instituted as an academic field in 1964, and areas such as television were increasingly regarded as important.

The first JlC-related one-off drama was Dare I Weep, Dare I Mourn? (1966), made by Associated-Rediffusion for ITV, shot on film and in the sort of vivid, verdant colour common in ITC and ATV series like The Avengers (1961-69) and Man in a Suitcase (1967). It features James Mason as the limping, troubled Otto Hoffman, and its broadcast was almost concurrent with the release of The Deadly Affair (1966), a mixed, if soundly moody film adaptation of le Carré’s debut novel, Call from the Dead (1962). This film also starred Mason as ‘Albert Dobbs’.

Dare I Weep… was adapted from a le Carré short story by Stanley Mann, who had written for Armchair Theatre. Its Toronto-born director Ted Kotcheff had helmed 28 AT plays and his career witnessed a curious trajectory: from directing Doris Lessing’s Play with a Tiger at the Comedy Theatre, London in 1962 to making Rambo: First Blood in 1982. [In 1971 alone this extraordinary director made the visceral Australian film Wake in Fright and that seminal Play for Today imbued with deep social conscience and dramatic force, Edna, The Inebriate Woman]

Dare I Weep… contains characteristic comments on the folly of the Cold War and individual human loneliness. Jill Bennett functions as something of a wish-fulfilment romantic interest as the virtuous rebel Frida. She is not as she seems, but is part of what is referred to as ‘The Movement’. Not with Larkin, Amis and Conquest, but an anti-Communist one on the east side of the Berlin Wall!

On 21 September 1966, Dare I Weep… reached 8.1 million homes, which equates to an estimated 17.82million actual viewers.[3] This calculates as a colossal 32.7% of the total UK population. It was fourth for its week in the TAM Top 20, a weekly record of the most watched programmes which had been published in the Financial Times since the early 1960s. For comparison, William Hartnell era Doctor Who averaged 8.5 million viewers, Steptoe and Son in 1963-64 regularly got 12-21million and The Forsyte Saga’s mean audience was 15.65 million. [It is worth noting that ITV’s TAM-meter system may have inflated the figures somewhat compared with the BBC’s Daily Viewing Barometers’ more conservative figures, which were based on attentive-viewing; see May (2023) unpublished thesis, I:132-135, freely downloadable here]

Guardian critic Gerald Fay was in two minds about Dare I Weep…; he extolled the ‘very spirited and talented performances’ of Mason, Jill Bennett and Hugh Griffith, but saw it as falling apart at the end.[4] The Observer’s Maurice Richardson was pleased by Bennett’s ‘pillar-box mouth’ but rather tired of Berlin Wall stories; for him, ‘the overall mood was so uniformly downbeat that I was more inclined to yawn than mourn.’[5]

By 1968, Armchair Theatre had begun a ratings resurgence; a bizarre Ken Campbell play One Night I Danced with Mr Dalton was seen in June by as many people as Opportunity Knocks, and was praised in the Express and the Telegraph for its ‘confident lunatic logic’.[6] That July, Thames replaced ABC and, when AT returned in 1969, its estimated average audience was 14.34 million.

Director Alan Cooke had helmed four Wednesday Plays, was to direct four Plays for Today and this was the last of no fewer than twenty-two Armchair Theatres he had helmed since 1959. He directed End of the Line (1970), which was le Carré’s only work written solely for television.

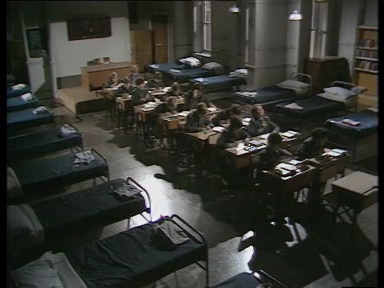

When interviewed in 2004 by Mark Lawson, le Carré mentioned his preoccupation with writing interrogation scenes that had ‘a measure of compassion and humanity’.[7] His first TV play represents this tendency, which was entirely missing from Dare I Weep… It is an exemplar of the economical studio-play, shot on video and, primarily, in one set, with very occasional filmed inserts. The two main protagonists are closeted in a first-class compartment within an East Coast Main Line train, starting in Edinburgh, terminating in London. 48 of the play’s 52 minutes are comprised of a duologue on a single set, broken only by the commercial break. Cooke handles the limitations of the setting rather well, with the nimble camera interrogating the characters.

While the play is primarily naturalistic, late on, there is non-diegetic sound that represents the mental anguish of Frayne (Robert Harris), on whom the MI5 agent-with-the-dog-collar-disguise Bagley (Ian Holm) turns the tables. This play functions as a sustained confessional, or battle of wills, between characters who do not appear elsewhere in the le Carré oeuvre. We get a sense of the humanistic, idiosyncratic approach to cross-examination that le Carré admires – in stark contrast to approaches taken by what he has described to Lawson as the ‘uninformed’ and ‘paranoid’ UK intelligence community today.[8] [Though, watching this again in 2023, I feel this needs qualifying, as the manner and means of Frayne’s removal at the end does not seem humane, but, is rather, casually disturbing]

End of the Line was broadcast at 8.30pm on Monday 29 June 1970, amid a prime-time schedule of networked ITV shows: following Opportunity Knocks, Coronation Street, World in Action; preceding a below-par Harry H. Corbett-June Whitfield comedy vehicle, The Best Things in Life. It competed with Panorama and The Troubleshooters on BBC-1 and, on BBC-2 an American Western series, The High Chaparral. 11.33 million viewers tuned in, down just over a million from the series’ third episode, but up from the opener, which had gained 10.3 million viewers [from TAM figures].

Critically, it received mixed reviews. In the Guardian, Nancy Banks-Smith disliked this ‘savage, sophisticated ordeal by rail’, not appreciating the erratic nature of the protagonists and finding it ‘disturbing’.[9] Henry Raynor in the Times was much more positive, commenting on le Carré’s ‘remarkably pointed, literary dialogue’, the lack of binary good-evil distinctions and ‘remarkable’ acting.[10]

The casting of the protean pair is ideal. Robert Harris, with his melodious tones, is Frayne, as English a traitor as they come: 70-year-old Harris had appeared in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and The Avengers (1969) and had played King Henry IV in a 1959 series. The role is comparable to John Le Mesurier’s Adrian Harris in Dennis Potter’s Play for Today, Traitor (1971) the following year – with the Dad’s Army star devastatingly imposing as the Philbyesque character. [As expounded in my historical analysis here,] Traitor creates a greater sense of antagonism between competing political ideas – though both Frayne and Harris have in common an intense, ambivalent attitude to England…

Ian Holm plays the more subdued MI5 agent – who aptly disguises himself as a priest to extract the confession from Frayne. This was just a year after his unsettling lead performance as an Al Bowlly fanatic in Dennis Potter’s brilliant, intense single-play for LWT, Moonlight on the Highway (1969). [Holm’s sole appearances in The Wednesday Play and Play for Today – Emma’s Time, 1970, and Soft Targets, 1982, were also notably in explicitly Cold War texts written by David Mercer and Stephen Poliakoff, respectively]

The rest of Armchair Theatre‘s 1970 run included plays by TV stalwarts such as Roger Marshall and Fay Weldon, and one by the sitting MP for Coventry North, Maurice Edelman. There was also the excellent Say Goodnight to Your Grandma by [the redoubtable] Colin Welland, very much in the style of John Hopkins’ plays of domestic disorder, who also contributed his third and last play for the strand. This particular series did well in the ratings: receiving an estimated average of 13 million viewers per play, according to TAM data. The largest television audience of the year, however, was for Miss World on 20th November, when 23.21 million people tuned into BBC-1 to watch the objectifying spectacle; not expecting to see scenes of Women’s Liberation protestors throwing smoke bombs and leaflets onto the stage and heckling the compere Bob Hope.

Fast-forward to British television, 1979: David Attenborough’s ground-breaking Life on Earth, the second runs of Fawlty Towers and Ripping Yarns. The irreverent Not the Nine O’Clock News quickly garnered acclaim akin to that of a contemporary Beyond the Fringe. In [its remarkably strong] years of 1979 and 1980 Play for Today included work by talents as various as Trevor Griffiths, Dennis Potter, Mike Leigh, Brian Glover, [Carol Bunyan], [Horace Ové & Jim Hawkins] and Ian McEwan. But before we get to the key TV adaptation of JlC, let’s focus on its key creative figures.

In a 1980 Times interview, director John Irvin speaks of being brought up in the same South Tyneside town as Ridley Scott: South Shields; as he says, “there must be something about the smell of the fish queues that produces film directors”.[11] In 1962, Irvin had received a £750 grant from the BFI to make Gala Day, an impressionistic portrait of the Durham miners’ annual Big Meeting in July of that year. This film had much in common with the Free Cinema movement of Lindsay Anderson and others, with its preoccupation with working-class culture, though this film is infinitely more approving of the carnivalesque behaviour of its subjects than Anderson’s scathing O Dreamland (1953).

In 1968, Journalist Arthur Hopcraft wrote a widely regarded classic of football writing, The Football Man. For Michael Wale in The Times, it was ‘the first clearly defined statement of the modern game’.[12] In the same year, he wrote in the Observer regarding the ‘banner of privacy’ that clubs were trying to apply to the game: ‘a field which has to be public or else it cannot exist’.[13] [This notably echoes the arguments made by literary scholar Andrew Hammond in British Fiction and the Cold War (2013) that British writers often represented public and private lives being lived in increasingly clandestine ways, in parallel to the era’s great geopolitical conflict.]

Hopcraft soon moved into television writing. which included an excellent, warm, subtle Play for Today, The Reporters in October 1972, featuring Michael Kitchen as an ambitious rookie journalist and Robert Urquhart as a down-at-heel veteran; both working at a paper in a provincial northern town. In The Observer, Clive James acclaimed its delicate pace and fastidious writing, saying it would make a good companion piece to a Dennis Potter play about journalism: ‘Potter all rage, Hopcraft all plangency.’[14]

[The (probably) Blackburn-set] The Reporters has evocative dialogue and settings – all fish and chips, 1970s boozers, references to Aldermaston marches, the Salvation Army and Dickens. Urquhart’s character describes Dickens as “the greatest of all reporters”, while expressing deep scorn for the modern popular press such as The Daily Express, which Kitchen ends up moving to work for.

Hopcraft became a prolific TV writer; he created and penned the bookending episodes of Granada’s Nightingale’s Boys, broadcast on ITV from January 1975: an elegiac series about a socialist Grammar School master (Derek Farr) who had served in the Spanish Civil War and stages a reunion for his favourite old class from 1949. In previewing this series in The Observer, Helen Dawson had described Hopcraft as ‘thoroughly dependable’.[15] In April of the same year, he completed his first television adaptation of a literary work: John Vanbrugh’s A Journey to London. In 1976, his play for Victorian Scandals: ‘Hannah’ focused on ‘that odd Victorian obsession with class and caste.’[16] In 1977, Hopcraft combined these two elements of adaptation and Victoriana when he adapted Dickens’s socio-political novel Hard Times, again for Granada, and shown in the Autumn. This adaptation, with a budget of £4,000 per televised minute, was not the last drama serial to be directed by John Irvin and written by Arthur Hopcraft to feature a circus…[17]

Virtually all broadsheet newspaper critics acclaimed Hard Times, and persistently throughout its run. Nancy Banks-Smith admires it as a ‘magnificent looker’ and in ‘some respects better than the book’ – giving the example of the performance and portrayal of the unfortunate Stephen Blackpool.[18] Clive James reviewed two of the four episodes, appraising the strong, gripping way Hopcraft puts across the novel’s ethical and political issues.[19] Chris Dunkley also praises it as fleshing out the symbolic elements of the novel and mentioned the hard choice drama viewers had between Play for Today on BBC1 and Hard Times on ITV.[20] All broadsheet TV critics commented warmly on production designer Roy Stonehouse’s work – ‘miraculously busy, teeming with detail’, according to James. Michael Church in the Times showed his political partiality in his disappointment that Hopcraft had ‘quietly but fundamentally redrawn’ Dickens’ odious union militant character Slackbridge ‘to suit the currently fashionable placatory attitude to militant trade unionism.’[21]

In 1978, Stanley Reynolds compared Hopcraft to Alan Bennett, seeing them as teledramatists who are ‘unmistakably English in an old-fashioned way’. [This remark sets the scene for Hopcraft’s version of JlC’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, which is widely regarded as an exceptional engagement with seedy and complex Englishness]

TTSS was shot entirely on film, not on video as was then the norm with BBC television period dramas or literary adaptations; like, say, I, Claudius (1976) [expertly directed by Herbert Wise in studio space]. It was produced in association with US film company Paramount and was one of several harbingers of the rise in TV drama co-productions on British television.

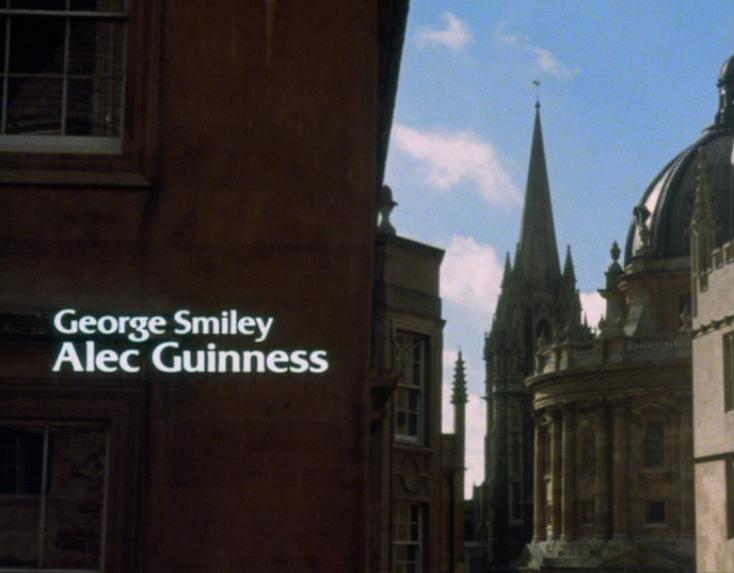

In Alec Guinness’ first significant television assignment, he spent six months working on it. Helpfully, BBC-2 screened a couple of his Ealing films on Tuesdays at 7pm in the direct run-up to TTSS’s broadcast: The Lavender Hill Mob (4 September) and The Ladykillers (11 September). [Piquantly, the BBC had purchased Ealing Film Studios in 1955, and were to use it for filmed material for the next four decades] As le Carré said, in a May 2009 interview with Mark Lawson, Guinness was ‘a hugely loved actor in Britain at that time’ and his 2% cut of the profits from Star Wars had secured him financially. In an interview with Tom Sutcliffe in The Guardian, published two days before the broadcast of episode 1, Guinness spoke of being impressed by how little Arthur Hopcraft had had to change the novel.

[Graphic designer Douglas Burd’s brilliant, minimalist and memorable title sequence establishes, and prepares us for, TTSS‘s tone. Geoffrey Burgon’s ruminative, minor-key musical ident, led by strings and woodwinds, circles, uncertainly, alongside the visual motif of Russian Matroyshka dolls, with one containing another and so on, in a traditional representation of a chain of mothers reproducing. Lighting Cameraman Vic Cummings masters interior lighting here, just like he did with exterior when working on the 1976-77 Play for Today title sequence. We also see names of many character players from the rich ensemble cast, like Ian Richardson and Beryl Reid, who are crucial in making JlC’s often elliptical text work in human terms]

[Furthermore, the end-credits contain Burgon’s thoroughly haunting, stately and lonely sounding ‘Nunc Dimittis’, sung by a choirboy]

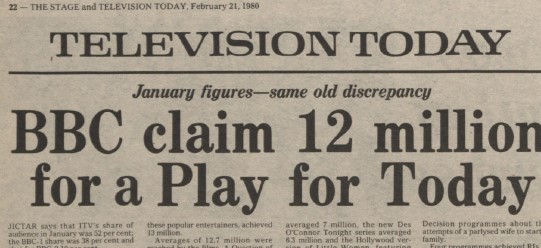

Multiple episodes of the serial were reviewed by several newspapers. That is, expect for The Times. Similarly to ITV, which was off-air for 9 weeks from the 6th August – it was affected by industrial action: going unpublished for nearly a year. Reviewing episode 1 in The Guardian, Banks-Smith admired the performances and atmosphere, describing Guinness’ Smiley as ‘a hero for our times’. [The ITV strike meant that all episodes of TTSS had no direct ITV opposition – barring the final Sunday repeat. This fact seriously bolstered TTSS‘s ratings, which were incredible for BBC-2: which ranged from 6 to 8.3 million, according to BBC data (BBC Audience Research Report, VR/79/482]. The entire series gained a high Reaction Index of 65 from viewers, though this was interestingly down on the average for individual episodes of 70 (ibid.).]

Hopcraft emphasises Bill Prideaux’s wistful telling of H.C. McNeile’s Bulldog Drummond stories to his pupils, when engaged as supply-teacher. The old patriotic certainties didn’t hold wide sway any more, at least pre-Falklands. Peter Tilbury’s downbeat sitcom, Shelley, with its over-educated and unemployed protagonist, played by Hywel Bennett, began closely prior to TTSS in July 1979 – and became a considerable ratings success. Its 1980 and 1981 series’ saw it gain audiences that ranged from 11 to nearly 16 million [according to TAM figures]. Bennett is well cast in TTSS as the seamy Ricki Tarr. The schedules seemed to be filled with dissections of Englishness, as Chris Dunkley argued in his review of episode 4. Eddie Shoestring was another down-at-heel, distinctly non-heroic character on BBC-1; BBC-2 had Jonathan Gill’s documentary series Public School and a sitcom called Bloomers, the last series to feature Richard Beckinsale – playing ‘an unemployed actor named Stan who goes into partnership with a florist’. Dunkley refers to TTSS as ‘a positive showpiece of Englishness’. [This may refer to the faded elegance of the varied locations used and its actors’ skilled rendering of complex and refined speech]

TTSS is, surely, a precursor to prestigious dramas like Inspector Morse (1987-2000) and The Jewel in the Crown (1984), which conveyed similarly ornate, yet ambivalent portraits of Englishness to expansive worldwide audiences. Dunkley locates TTSS as different to, on the one hand, the glamorous Scarlet Pimpernel and James Bond-style depictions of spies, and, on the other, the pathetic and sordid type represented by the character Lonely in ABC and Thames’ long-running espionage drama Callan (ITV, 1967-72).

Dunkley agrees with James that TTSS‘s plot is slow moving, but he commends the serial’s focus as ‘closer to anthropology […] we are being shown the enclosed society (The Circus) within a society (Post-War Britain) which earlier harboured Kim Philby.’ TTSS does indeed have a comparable focus to Dennis Potter’s aforementioned ‘Traitor’ and Granada’s documentary-styled drama, Philby, Burgess and Maclean (1977) – a sturdy, inelegant representation of the real-life events, with compelling performances from Derek Jacobi as a camp, acerbic Burgess and the stalwart character actor Anthony Bate as an unflappable Philby. Surely Powell and others had this association in mind when they cast the lugubrious Bate as the mandarin and overseer Oliver Lacon in TTSS. Bate is one of relatively few actors to return in Smiley’s People (1982).

In the Observer, Clive James mentioned the ‘dull’ trailers, which featured Arthur Hopcraft strolling Hampstead Heath and insinuating that anyone around could be spies! James didn’t like the programme either, seeing the dialogue as stilted; for him, there is too much emphasis on character and too little on plot. However, by episode 4, he was declaring it ‘a good deal less wearisome’. For James, Hopcraft does capture what is best in le Carré: a ‘unique […] romantic dowdiness which nobody else can quite match’. While he says it is ‘only marginally better than plain dull’, he does concede, as a subjective viewer, that he will watch to the end.

Peter Fiddick’s review of episode 7 was highly personal, bemoaning that his wife, having previously read the novel, had spoiled his enjoyment of the guessing-game by telling him the traitor’s identity. Fiddick discerns that Hopcraft deals well with the inevitable division of the audience into the ‘Knows’ and ‘Don’t Knows’ – i.e. those who had read the novel and those who had not. He astutely observes how Hopcraft, contrary to Guinness’s perspective that he barely changed anything, shifted the chronology of the events surrounding Bill Prideaux to keep the ‘Knows’ guessing and uncertain.

Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of ‘cultural capital’ can be applied to Dunkley’s retrospective stance on this serial, which is culturally refined, or pompous, depending on your perspective: ‘[TTSS] has the same sort of satisfying logic and symmetry as a good crossword or a Bach suite.’ In the same extended piece, Dunkley praises the BBC and derides the section of the audience who were resistant to the appeal of TTSS: ‘Goodness knows what all the inverted snobs will do now that they can’t spend the week boasting about their inability to follow a single minute.’ His high cultural tastes according with a distaste for rank misogyny, Dunkley understandably takes some delight in the fact that the same industrial dispute by BBC technicians which had affected editions of Doctor Who, Tomorrow’s World and Newsnight had also thwarted the broadcast of Miss World 1979. Clearly, cultural capital in 1970s Britain was accrued by ‘getting’ such programmes as TTSS and denouncing the more egregious popular shows.

TTSS was named the best drama series in the annual Broadcasting Press Guild awards, decided by television writers and critics and, unsurprisingly, Alec Guinness won the best television actor award for his magisterially subtle portrayal of George Smiley which anchored the whole production.

TTSS was popular in an era when popular programmes were regularly good, or, ascribed with ‘value’ by many. On BBC1, for example, the crime drama series Shoestring, with Trevor Eve as its pacifistic, provincial detective, series one of which averaged about 17.1 million viewers, [aided somewhat by the ITV strike]. While David Wheeler of The Listener did not like it, the same publication’s Andrew Sinclair praised its eccentricity, originality and attention to social problems.[22] He quotes the essayist Joseph Addison’s view that the good and the popular are intrinsically linked. Peter Smith, who directed episode five of Shoestring‘s first run, ‘Listen to Me’, went onto direct A Perfect Spy eight years later.

TTSS’s producer Jonathan Powell was responsible for further literary adaptations, Testament of Youth and Pride and Prejudice in early 1980, which completed a trio of ‘astonishing’ productions, in Dunkley’s view, [whose response strongly approves of the BBC’s long-term provision of perceived high-quality literary-sourced period dramas].[23] Interestingly, given debates regarding ‘value’, it was Powell who, with Michael Grade, proved the nemesis of Doctor Who in the mid-1980s. In his role as Head of Drama Series and Serials he gave the show little support or encouragement (see Marson, 2013).

John Hopkins co-adapted Smiley’s People (1982) with le Carré. In 1966, Hopkins had written the masterful four-part drama of domesticity and clashing values, Talking to a Stranger, in 1966; in October 1976, the serial was, aptly, shown as the centrepiece of the first ever public retrospective of British television drama at the NFT.[24] Hopkins had written many vivid Wednesday Plays, such as Horror of Darkness (1965), a striking, sensitive and intense chamber drama about a gay man’s role in a tortuous love triangle; [this brilliant drama with Alfred Lynch, Nicol Williamson and Glenda Jackson appeared] two years before the Sexual Offences Act 1967. Curiously, another of his assignments involved contributing to the James Bond jaunt Thunderball (1965). Simon Langton directed, John Irvin having moved to Hollywood straight after TTSS, to direct the likes of The Dogs of War (1980), a war film about mercenaries adapted from a Frederick Forsyth novel, for which he enlisted Geoffrey Burgon for the underscore.

[Smiley’s People has an ingenious, if perhaps more arcane, title sequence than TTSS‘s. Stewart Austin’s award-winning design – following TTSS‘s similar accolades – shows the chalked lines on the park bench, a spy tradecraft signal: this, along with the meticulously peeling coloured paint on the wooden bench, feels peak JlC in its drab realism, saying to us: these are the authentic rules of the game. There’s stately, but dramatic, subtle changes in lighting and slow camera movement create an intriguing atmosphere, which feels more arty, but also prosaic, than TTSS‘s Matroyshka dolls. It ends with an explosion, highlighting the potential for danger ahead. This sequence retains the focus on the actors, starting with ‘ALEC GUINNESS IN’, and then also listing six other key actors, including Bernard Hepton, Rosalie Crutchley and Patrick Stewart. Patrick Gowers’s musical ident feels like a mildewed, slowed-down version of Burgon’s musical textures, strings sounding thoroughly diseased and weary, lead horns processing forlornly and sinisterly; the deathly drift is barely disturbed even by the climactic tympani used for the explosion. This piece’s title, ‘Ostrakova’ evokes Eileen Atkins’s character.]

Smiley’s People was given a prime space in the late autumn-winter 1982 schedules, 8pm, and averaged between 7-8 million viewers; often topping BBC-2’s own chart, and a remarkable figure given the lack of ITV strikes. Banks-Smith found the series ‘less compulsively mysterious’ than TTSS; the Times’ Dennis Hackett liked the interplay between Smiley and the ‘cannibalistic careerist’ Lacon. The Guardian’s Martin Walker praised the cast but felt disappointed, writing his review in the second-person to Smiley: ‘They begin your credits with some trash that sounds as if it had been warmed over from a spaghetti Western […] The mood is changed and the mood was all [my emphasis].’ The end credit-sequence is utterly overshadowed by that of TTSS, which had Geoffrey Burgon’s melancholy choirboy music. In the Financial Times, Anthony Thorncroft saw it as ‘a triumph of style over content’, though Dunkley thought it ‘outstandingly good’, if more conventional than TTSS.

A Perfect Spy (1987) was another co-production, and earned significant overseas sales for BBC Enterprises in an era when the Corporation was moving towards a more ‘hard-headed commercialism’, [spearheaded by whizz-kid accountant Michael Checkland, whose steadiness has been praised by Jean Seaton (2015)]. It saw the return of Hopcraft as adaptor and achieved solid ratings for BBC-2: 5.55 million for episode 1, and 4.9 and 4.1 million for its other two appearances in the channel’s weekly Top 10.

[I haven’t actually seen all of A Perfect Spy, so can’t thoroughly assess it myself, but I can analyse its titles. There is a feature film-like use of a preceding, nearly two minute dramatic scene before the tile sequence begins. Mildly foreboding strings play a brief, lamenting, violin-led ident; its 27 seconds or so are not accompanied by any substantive visuals, just a few credits and the series title in white formal typeface on a blank black background. The previous two adaptations’ focus on an acting ensemble goes: we only seen ‘STARRING RAY McANALLY’, no one else. This bare anti-aesthetic represents either bullish confidence in the JlC moniker to pull viewers in on its own terms, the BBC responding to its perennially straitened economic conditions, or, simply, a baffling lack of effort – or maybe it’s a bit of all three?! The end credits, also simply with white text on black, feel very late 1980s or early 1990s, with Midi synths and piano, joined belatedly by violin, feeling a blander variant on Barrington Pheloung’s lushly ornate TV music.]

The Times’ Peter Waymark acclaimed Hopcraft’s ‘strong script’; all reviews endorsed Ray McAnally and Peter Egan. [The former was soon to star in A Very British Coup (1988), Alan Plater’s skilled adaptation of Chris Mullin’s political counterfactual novel]; the latter was famous contemporaneously as the urbane Paul Ryman in Esmonde and Larbey’s melancholy sitcom Ever Decreasing Circles (1984-89). However, Hugh Hebert in The Guardian described it as a ‘lugubrious, plodding tale’, unfavourably comparing it with Potter’s The Singing Detective (1986) as an exploration of father and son, past and present. Andrew Hislop found it ‘an unforgivable error’ to alter the novel’s complex chronology and proceed chronologically through Pym’s childhood. However, in The Listener, Peter Lennon thought it ‘overlooked’ and ‘the outstanding serial of the year’.[25]

1980s television drama saw the eclipse of the single-play. It was cheaper and easier to make series and soap operas, due to their recycling of actors, costumes and sets – and their [generally being a safer bet to achieve higher audience sizes]. While academic George W. Brandt (1993) saw much hope in the series and serials, Alan Plater foresaw in 1989 the long-term damage that would result from the single-play’s demise, arguing in the Listener that ‘We must battle for original work’. Plater himself had – literally – adapted; fashioning an acclaimed BBC serial like the Trollope adapation The Barchester Chronicles (1982) alongside producer Powell, alongside his own deadpan, warmly socialist humanist Beiderbecke trilogy for Yorkshire Television (ITV, 1984-88). Indeed, the older generation of writers made magnificent serials in this era: Beiderbecke, Edge and Darkness (1985) and Potter’s aforementioned The Singing Detective surely constituting the pinnacle.

However, opportunities were now denied to younger writers. Following the cancelling of Play for Today in 1984 and the gradual whittling down of other single-play strands – aspiring young writers could not learn and experiment, as Plater had been able to. Young British people in 2013 know the feeling, living through the educational policies of Michael Gove. [The Play for Today ethos actually outlived the ‘PfT’ strand banner, as original, contemporary-set one-off dramas did persist on BBC-1 and BBC-2 prime-time until 1991, at least; though it had disappeared as a regular fixture by the end of the 1990s]

The success of the le Carré adaptations was surely a factor in the commissioning of TV serials that depicted self-serving establishments, corruption and intrigue: Muck and Brass (1982), Edge of Darkness, The Monocled Mutineer (1986), A Very British Coup and Traffik (1989). However, more influential today seems to be the nostalgic heritage period drama of John Mortimer’s Brideshead Revisited (Granada for ITV, 1981) and Julian Bond’s The Far Pavilions (Goldcrest and HBO for Channel 4, 1984), stretching forward to Downton Abbey [(Carnival Films and WGBH-TV for ITV, 2010-15)].

In April 1991, JlC’s own feature-length adaptation of A Murder of Quality gained a sound audience of 10.99 million on ITV, helmed by a notable arts documentarian and Play for Today director Gavin Millar.[26] While it was comfortably defeated by The Darling Buds of May, Prime Suspect and the big soap operas, it was more popular than mainstream propositions like Russ Abbot, Davro, Little and Large, Top of the Pops and A Question of Sport. AMOQ was made by Thames; over 20 years after the same company had produced End of the Line. Thames was only to broadcast for another year, falling victim to the Thatcher government’s 1990 Broadcasting Act, a deregulation of the Independent Television franchise system which has led directly to the market-driven, culturally-impoverished state of ITV of today.

A Murder of Quality reflects the shift towards the only one-off TV dramas becoming single docudramas or biographical dramas not gathered in a strand, being part of film-centric strands, or like this: one-off TV movies. Stanley Myers, a key composer straddling the worlds of Hollywood and the Wednesday Play-Play for Today, provides an underscore which builds on some of the atonal modernist classical sounds he evokes in David Pirie’s late Play for Today Rainy Day Women (1984).

With AMOQ, Le Carré finally became sole adaptor of one of his own works, twenty-six years after he had told Muggeridge on BBC-2 that he wouldn’t do so. The varied cast included skilled veterans of Armchair Theatre and The Wednesday Play: Billie Whitelaw, [David Threlfall, Joss Ackland, Denholm Elliott] and Glenda Jackson [- alongside a teenaged Christian Bale!] The Guardian’s Matt Sweeting saw it as dated: ‘anything scruffy looked like as though it had been sprinkled with 30 year old dust […] A good Morse would run rings round this’.[27] Lynne Truss of The Times thought it a predictable and ‘conventional murder mystery’, involving ‘mundane detective work’.[28] In stark contrast, JlC adherent Chris Dunkley, still at the FT, commended the ‘outstanding’ cast – featuring Threlfall of future Shameless fame and Elliott playing George Smiley – and valued its concerted focus on the English class system.[29]

[Since 2013, le Carré remains a regular source for film adaptations and, notably, his work has become at home on BBC-1 as attested by prestigious, ‘high-end’ thriller series like The Night Manager (2016) and The Little Drummer Girl (2018).

[The title sequence of The Night Manager aurally contains busy, Hollywood strings and jauntily foreboding bombast. Visually, we see non-human objects, focused on often in high definition close-ups akin to expensive advertising imagery. We see rockets, drinking glasses, cups of tea, planes, fireworks, boats, missiles, a lamp (?); culminating in a chandelier which explodes, evoking a shift in focus from the pyrotechnics of Smiley’s People‘s title sequence, with its richly drab espionage particulars towards moneyed, super-rich lifestyles. The music sounds oddly generic, but clearly prepares people for a globe-trobbing adventure that will include suspense and action; a popular thriller, that does not flag up any bleakness or political themes.

The Night Manager was, unquestionably, compelling, combining Jed Mercurio-like populist suspense with its highly elite public-schooled cast who adeptly embodied the corruptions of the globalised Blair-Bush-Clinton era. In terms of audience sizes, TNM was a vast success, outscoring the latter adaptation in the popular zeitgeist. However, as I argued here, director Park Chan-wook and the exceptional Florence Pugh ensured that TLDG had greater artistry and deeper, more trenchant political insights than TNM, and was a vast improvement on George Roy Hill’s 1984 film version.

The Little Drummer Girl‘s titles shift back, musically, towards the slow and melancholy, being led by a delicate, rueful Spanish guitar. We see empty cinema seats. Rarely, for a JlC title sequence, characters appear: Florence Pugh’s Charlie clutching a suitcase, her blonde hair blowing in the wind in ultra-slow motion. She is fashionably dressed, standing in front of grey high rise buildings in a city. We see a partially concealed monochrome photo on a desk, a man’s back and his shadow on the wall, a phone on the ground – evoking disarray – an aerial shot of a red car driving on an urban road, paused, like everything else here. A modernistic clock with steel hands, the seconds moving by. A moustached man turns to us, a tape recorder spoils. We return to Charlie, back to back with an indistinct woman, and then see a lone bag on the ground through a doorway. This sequence returns us to a more drab urban JlC aesthetic, with a stately, dense patchwork of paused images; amid the intrigue we know we will follow a modern woman protagonist within a primarily urban setting, with the prominent suitcase and bag suggesting Charlie will travel far.]

Ultimately, television, [with its innate intimacy and situation within the domestic environment] has proved an ideal medium to depict non-heroic protagonists. It has thoroughly represented David Cornwell’s systemic analysis of the British intelligence world, with its flawed protagonists, searching interrogations and sense of moral malaise that can be more broadly applied to British power structures in the 1970s more generally [and, unarguably, even more so today]. Also, Le Carré on television reflects the history of television: a move away from single-plays towards series and serials. [While longer-form dramas have sometimes delivered great depth and richness, the economically-driven shift to this form has, unfortunately, denied writers sufficient scope to develop their individual styles, therefore depriving us of dramas which give voice to contemporary life in the UK. In his own way, Cornwell was emphatically part of this tradition back in 1970 with End of the Line. It’s about time we revived it.]

–With thanks to Joseph Brooker and Ian Greaves, for their vital support in enabling this research.

[1] Stevenson, R. (2004) The Oxford English Literary History Vol.12 1960-2000: The Last of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.45

[2] Caughie, J. (2000) Television Drama: Realism, Modernism, and British Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.29

[3] No author (1966) ‘TAM Top 20’ , Financial Times, 10th October, p.7

[4] Fay, G. (1966) ‘Television’, The Guardian, 1st October, p.6

[5] Richardson, M. (1966) ‘Keeping Frost in balance’, The Observer, 2nd October, p.25

[6] White, L. (2003) Armchair Theatre: The Lost Years. Tiverton: Kelly Publications, p.219

[7] BBC Radio 4 (2004) ‘Front Row: John le Carré’, TX: 31st August

[8] BBC Radio 4 (2009) ‘Front Row: John le Carré’, TX: 22nd May.

[9] Banks-Smith, N. (1970) ‘The End of the Line’, The Guardian, 30th June, p.8

[10] Raynor, H. (1970) ‘Liberation from Bondage’, The Times, 30th June

[11] Preston, J. (1980) ‘John Irvin’s move to the big screen’, The Times, 20th December

[12] Wale, M. (1968) ‘Sports books: Amateurs’ kingdom’, The Times, 14th December

[13] Hopcraft, A. (1968) ‘The Football League v The People’, The Observer, 4th February, p.20

[14] James, C. (1972) ‘Bananas with the Duchess’, The Observer, 15th October, p.37

[15] Dawson, H. (1975) Briefing: TV Guide’, The Observer, 12th January

[16] Dunkley, C. (1976) ibid.

[17] Church, M. (1977) ‘Unparalleled prodigality for Dickens’, The Times, 26th October

[18] Banks-Smith, N. (1977) ‘Hard Times’, The Guardian, 26th October, p.10

[19] James, C. (1977) ‘The smell of seaweed’, The Observer, 30th October, p.31

[20] Dunkley, C. (1977) ‘A Beautiful Harvest’, Financial Times, 9th November

[21] Church, M. (1977) ‘Love for Lydia’, The Times, 2nd December

[22] Sinclair, A. (1979) ‘The good and the popular’, The Listener, 22nd November

[23] Dunkley, C. (1980) ‘The serial’s the thing’, Financial Times, 30th January

[24] Dunkley, C. (1976) ‘An above-average year’, Financial Times,

[25] Lennon, P. (1987) The Listener, December, p.33

[26] Fiddick, P. (1991) ‘Research’, The Guardian, 29th April, p.23

[27] Sweeting, A. (1991) ‘Television’, The Guardian, 11th April, p.28

[28] Truss, L. (1991) ‘Television: Sleepers/A Murder of Quality’, The Times,

[29] Dunkley, C. (1991) ‘Prix Italia goes feminist’, Financial Times,