This article is the first of a series on what I saw at the Spying on Spies conference at the Warwick Business School on the seventeenth floor the Shard, London, 3rd-5th September – ably organised by Toby Manning and Joseph Oldham, who has written a far conciser conference report than myself here! Evidently, one human being can only gather so much of the total output of the conference, but the Facebook group is yielding many of the papers that I missed, which I may also comment on in time. I witnessed nineteen papers, plus three keynote speeches, making a total of 22. This was a mere 41.5% of the total number of 53 speakers at the conference. The articles intend to follow a chronological path, and aim to encapsulate what I learned about the Cold War through the voices of fellow SOS delegates.

My own paper, which I have previously linked to, is here.

THURSDAY

The opening remarks were brief and germane, setting out the conference’s remit to the 55-60 or so people in attendance at the beginning. The word ‘cross-disciplinary’ was mentioned; always, I feel crucial that supposedly ‘discrete’ disciplines are not placed in silos, but can intermingle. Important also, among these particulars, was mention of the later pint-meal convening in the George Inn, Borough Street, after Thursday’s panels. There was an allusion to a quiz and prizes by the end of the conference. Oldham’s making reference to Callan and The Sandbaggers was intriguing to me, having been captivated by the latter in recent viewings of Network’s DVDs. Unfortunately I was to be unable to see Oldham’s paper on the Cambridge Spies on TV, due to being on helper duties for my first panel of the conference… As ‘helper’, I assisted in a technical support role, and witnessed all Thursday’s papers in the Syndicate I-III, a non-Arthurian ‘round-table’.

The first panel I attended, then, was on ‘Postmodernism and the Spy Genre’… chaired by Oliver Buckton, who was to be part of my panel on Saturday.

Kyle Smith (University of Highlands and Islands, UK) began proceedings in animated style, comparing two literary works: E. Phillips Oppenheim’s Miss Brown of X. Y. O. (1927) and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). There was reference to the ‘sleepy state’, ‘conspiracy’ and ‘apocalypse’ narratives’ presence in EPO’s novel, which revolved around a Communist plot against the British state.

There was mention of Duncan Sandys; I cannot recall the exact context from my vague notes! But I did recall that Sandys was responsible for the 1957 Defence White Paper which reduced conventional forces in the move towards the missile age, and also set in train the end of National Service. Smith linked Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) with futuristic Seattle, with its early 1960s World’s Fair – Pynchon had worked in Seattle. He analysed the novel’s depiction of architecture as controlling and discussed the internationalism of transnational, bureaucratic states – the ‘rocket-state’, indeed. Gravity’s Rainbow’s protagonist Tyrone Slothrop was said to be unwilling to be an information machine – a concern ever more relevant with post-1973 economic shifts.

It is often very difficult to follow academic papers on novels you haven’t read, but I learned a lot and came away wanting to read both novels. Smith made a point that stayed with me: he quoted General Leslie R. Groves, military head of the Manhattan Project, on compartmentalisation of knowledge being good – and then linked this disturbing tendency with Pynchon’s text, citing the line: ‘Everything he needed to do his job and nothing else’.

Eugenia Gresta (George Washington University, USA) was not in attendance, but Buckton read the paper. It focused on Boris Akunin’s writings, including The Turkish Gambit, with its postmodern shifting between the 1877-8 Turkish-Russian War and the Khrushchev era thaw; its focus is on de-Stalinization, ideology and propaganda. There was a mention of ‘Russians turning inwards’, towards ‘Mafia activities’, which put me in mind of the tremendous, bleak film Leviathan (2014). Akunin was said to have written epic political series’ of novels, set in 1931-83 and 1966-88.

There was reference to the narrative ‘fading into an artifice’; Gresta used phrases like ‘literary anarchy’ and ‘a postmodernist mosaic’ to describe Akunin’s approach. His novel has a Russian nobleman and civil servant as the hero and the Turkish spy as the villain. To the Soviets, ‘spy / spion’ had negative connotations, ‘secret agent’ had positive. The character Petrovich dresses like an English gentleman, linking somewhat with the portrayal of Adrian Harris in Dennis Potter’s Play for Today: Traitor (1971), which I was to analyse on Saturday.

Anna Suwalska-Kolecka (The State School of Higher Professional Education in Plock, Poland) gave a paper which was rare in the conference for its focus on drama. Her focus was Tom Stoppard’s 1988 play Hapgood, with its focus on twins, spies and quantum mechanics. Stoppard’s link between QM and espionage is said to reflect the intricacies of human identity. The play focuses on the British secret services and the CIA setting a trap for the mole who betrayed them to the KGB. Suwalska-Kolecka’s mentioned Stoppard’s creation of deliberate confusion with bizarre stage images; his evoking of the interrogative “What exactly is going on?” This somehow evoked in my noggin the recent re-viewings I’ve undertaken of that wonderfully absurdist dystopia of British television, The Prisoner (1967-68).

As with that series’ public tannoy announcements, there is an articulated meta-narrative, but this one doesn’t cheerily conceal: “In science this is understood: what is interesting is to know what is happening.” In contrast to Newtonian fixed laws dependant on ‘cause and effect’, QM theory has nothing as certain. Suwalska-Kolecka saw Stoppard as having linked this greater uncertainty and the (supposed) collapse of the metanarratives such as Marxism, and mentioned his utter distrust of binaries. There was a reference to the crisis in epistemology, and the typical postmodernism of ‘no one authoritative voice’.

Q&A:

When asked why he’d chosen that particular Oppenheim novel, Smith admitted there could have been good selections from John Buchan, Helen MacInnes and Geoffrey Household. However, he said its focus on a female protagonist – Miss Brown is a secretary – made it stand out, as well as its contrast to the 1970s with its view of ‘the worst thing that can happen is that the [British] Empire is destroyed’.

When asked about Pynchon’s use of third parties as ‘puppet-masters’, Smith stated that Pynchon didn’t like definite answers. He then mentioned the bizarre character who thinks he literally is World War II! Who then gets a temperature on D-Day… Returning to the Oppenheim novel, he said that the novel naively intimates the winding-up of MI5 at its close, once the threat has been defeated and a peace has been made with the Communists. I then mentioned Bernard Porter’s Plots and Paranoia, with its survey of the British reluctance to engage in espionage on any seriously wide, organised scale until WW1.[1] Therefore, the prospect may not have seemed entirely naïve at the time. Porter has commented that it was a mark of our confidence in the Victorian age that the British felt they didn’t need any organised spying. I then asked about whether there was any reference or link to the 1926 General Strike in Oppenheim’s novel. Smith said there wasn’t, it being primarily a romance rather than a ‘serious’ spy novel. He said there weren’t left-wing or communist villains in Bulldog Drummond and that Sapper claimed communist ideology didn’t exist! The villains tended to be pawns of industrialists, wanting revenge against Britain, reflecting a ‘motiveless malignity’.

I did vaguely think of Agatha Christie here, having read about The Big Four (1927), in which events such as the October Revolution have been steered by a shadowy gang most of whom are hiding out in the Dolomites: an American richer than Rockefeller, a French woman scientist, a spectral Chinese mastermind who never sets foot out of China and an obscure English actor and master of disguise known bizarrely as ‘The Destroyer’. To quote from the novel: “There are people […] who know what they are talking about, and they say that there is a force behind the scenes”. … “A force which aims at nothing less than the disintegration of civilization. In Russia, you know, there were many signs that Lenin and Trotsky were mere puppets whose every action was dictated by another’s brain.”[2]

This tendency interested me; it crops up enough in shadowy-conspiracy TV dramas like Undermind (1966), which is equally careful about precisely naming the ideology of its inscrutable conspirators. An intense ‘Yellow Peril’ politics can clearly be discerned in Christie’s positioning of Li Chang Yen as the Fu Manchu-style ‘mastermind’ behind the Big Four’s plan to create worldwide anarchy and then take over.[3]

Suwalska-Kolecka was asked about Hapgood’s staging in Poland and translation and said that much of Stoppard’s humour was lost when converted into Polish, but also that Polish TV broadcast a large amount of drama and theatre. She also mentioned Stoppard’s Jumpers (1972) exploiting detective fiction. She spoke seeing the Gdansk premiere of Arcadia and referred to TS’s frustration at the predictability of most novels; thus, he turned to modern science for what he saw as greater volatility. There was interesting mention of Shakespeare’s foreshadowing of unstable theatrical identities, with his comedies of misunderstanding and characters donning disguises. I am currently teaching King Lear at GCSE; a tragedy which has uncertain identity as a significant theme.

Next up, in the largest lecture theatre, was the first Keynote Speaker, Phyllis Lassner (Northwestern University, USA), who has had a distinguished academic career and has published two books on Elizabeth Bowen and one that I’d like to read some day: Women Writing the End of the British Empire. As Lassner states in her abstract, her Keynote aimed to ‘challenge the common assumption that the politics of spy fiction are only a pretext for adventure plots […] for Helen MacInnes and Ann Bridge, political crisis is the plot that drives the thrills and chills of spy fiction’.

Lassner focuses on MacInnes’s novel Above Suspicion (1941), commenting on how the writer perceived critique and leadership as overly male dominated domains. She identifies radicalisms: at the centre of this novel is a woman’s voice, peoples’ right to self-determination is desired, instead of the sort of defence of Empire seen in Ian Fleming. There’s an interweaving of events in1939 and 1941 and a potent challenge to the Nazi representation of Jewish prisoners as ‘sub-human’: the novel’s protagonist Frances sees them as ‘civilised’. Lassner discusses the novel’s view that ‘if only the people of Germany had acted against the Nazis’, thus foreign involvement would not have been needed. She uses Haffner’s Defying Hitler memoir to explain how stacked the odds were against internal rebellion, given the appeasement tendency. Lassner summarises with a claim that MacInnes identified signs of the genocide to come.

She then analysed Ann Bridge’s 1953 novel, A Place to Stand. This was said to revolve around a portrait of 1940-1 Budapest, Hungary’s joining of the Axis and American isolationism. There is also mention of the Katyn Massacre of Poles by the Soviets during WW2; Lassner placed the number of Polish dead at 30,000. She then drew a link between the refugee situation and the Syrian crisis, dominating the news during the conference. There was discussion of motifs such as false identity papers and the nature of resistance, and how the novel was ‘politically and narratively’ caught between mourning a lost Europe and hopes for US and UK intervention.

Q&A:

Lassner discussed how Bridge critiques the place of women in narratives. A question regarding Fleming’s Casino Royale – which, it was noted, was published the same year as APTS – led to interesting discussion of how the character Vespa turns out to be far more complex than Bond suspects. This was said to be more complex than the ‘formulaic’ women of the early Bond films. A greater vulnerability was discerned in Skyfall (2012), which was said to be closer to Fleming’s Bond. Lassner mentioned how Bond is often a ‘hapless’ figure in the novels and regularly doesn’t win. She made strong final claims for MacInnes and Bridge’s work as reacting against the xenophobia of earlier writers, and avoiding the Oppenheim/Buchan binary of women as villainess or ‘help me’ figurine.

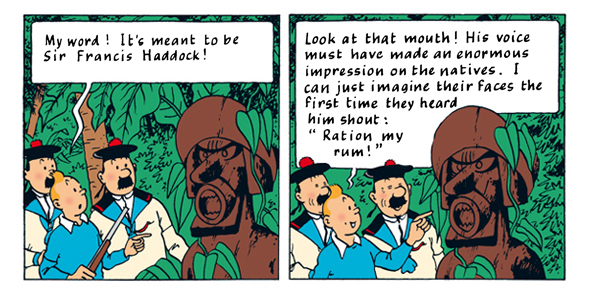

The early evening panel saw me back in Syndicate I-III. Surangama Datta (University of Delhi, India) gave a paper clearly influenced by Edward W. Said’s theory of ‘Orientalism’; she contrasted Herge’s Tintin and film director-writer Satyajit Ray’s Feluda, using binary terms. Tintin was placed as problematically imperialist in its ideology; having a ‘Eurocentric’ approach and seeing different cultures as “Other”. Red Rackham’s Treasure (1943) and Prisoners of the Sun (1946-48) were the two narratives analysed. The former was said to represent the native via a stereotypical cannibalism, signified through skulls and bones being strewn around the island. Tintin and Haddock are portrayed as more idiosyncratic individuals in comparison to the uniform natives, whose story and perspective we never get. Haddock is even lionised in statue form: ‘Sir Francis Haddock’.

It simply cannot be an academic conference without the verb ‘problematise’ showing up, and Master’s student Datta took the honours for the first such usage of SOS! I was also to partake of such lexis.

The Seven Crystal Balls (1946-48) was said to depict Tintin as a beacon of scientific knowhow, as opposed to the unreliable, superstitious Peruvian natives. Datta identified what she saw as a binary of EAST (Occult) : WEST (Scientific). She made a formal observation about the clear distinctions between the cartoon adventure’s panels reflecting the clear-cut content. This was contrasted with the artwork of Tapas Guha, for Ray’s Bengal-set Feluda mysteries – Guha has the action burst across the panels: linked in the paper’s argument with the resistance of oppression. I would have appreciated more time allocated to Feluda; it was a little under-analysed in comparison to Tintin; but, still, clear points were communicated.

Doruk Tatar (University of Buffalo, USA), a third-year graduate student discussed the novels The Black Book (1994) and My Name is Red (2001), by Nobel Prize-winning Turkish author Orhan Pamuk. For context, he discussed Kipling’s focus on the geopolitical ‘Great Game’ and Edward W. Said’s critique of Kim and its white fantasy of ‘going native’, as well as Arendt’s The Human Condition – regarding our fascination with numbers and letters showing our compulsion to feel part of something bigger. He also discussed Frederic Jameson’s distinction between the receding public sphere and the private sphere. Tatar located the conspiracy aesthetic as being of the twentieth century – while, in the nineteenth, espionage had been articulated as a ‘game played for its own sake among colonial secret agents’. Conspiracy was viewed in context of the enlargement of the private sphere. It begged the pertinent question: how does the withering of the welfare state in Western societies affect people’s private worlds?

He situated Pamuk’s portrayal of transnational corporations alongside David Harvey’s critique of neo-liberalism. He also very pertinently mentioned how the economic ideas of the ‘Chicago boys’ were first exported to Chile, and referred to this as a “laboratory of Thatcherism”, which the excellent Andy Beckett has written extensively about.[4]

In Tatar’s biography in the conference programme, he mentions how the term ‘conspiracy’ is used to posit affective connections between individuals and ruling elites and usually excludes ‘social antagonisms’ and thus paradoxically enforces ‘a sense of harmony within post-colonial societies’. He cited Walter Benjamin regarding how Pamuk views everyday objects as having ‘unconventional meanings’ and harbouring ‘conspirational agendas’. TBB has a flaneur-type detective investigating how seemingly innocuous objects are ‘essential in shaping the habits of the society in the most sinister way’. MNIR depicts the monetary coin as effectively having character, with the worker estranged and stripped of agency. I liked Tatar’s focus on ideologies and representations of everyday life.

Samuel Goodman (Bournemouth University), focused on James Bond and Popular Culture after Empire, mentioning in an aside how apt it was to present his paper in London, a centre of imperialism. Bond – Fleming’s, Amis’s and Boyd’s, among others – was seen as bound up with nationhood and Britishness. Goodman pertinently mentioned Danny Boyle’s usage of Craig’s Bond in the 2012 Olympics promotional film – with the signification of Bond as quintessentially English, the fictional spy appearing in shot alongside the serving monarch. The difference from the 1948 Olympics was clear to Goodman; then: world power status assertion, now: inclusiveness, as signified by the Parade of Nations. He persuasively described Elizabeth II and Bond as cut from the same cloth: both implicated in this status decline, both being born in the public consciousness in the 1950’s.

Unlike Dominic Sandbrook in his recent TV ‘history’ show Let Us Entertain You, Goodman avoided ducking the issue of American influence. He mentioned Dr No’s plan to disrupt US missile tests, and how Fleming saw British colonies as buffers against communism. Casino Royale focuses on Marshall Aid; Goodman mentions the irony that Lend Lease debt was finally paid off in 2006 – the year of the Craig version of the same novel!

He mentioned the ‘fiction of a civilising role’ and the ‘exotic mode of aesthetic experience’ in Bond’s consumer enjoyment. Two months later, on Saturday 7th November, I was to see Goodman deliver a talk as one of the ‘New Generation Thinkers’ at the BBC Free Thinking Festival at Sage Gateshead, which entertainingly explored the British Empire’s influence on British consumption and production of beer.

Q&A:

A delegate mentioned how Fleming entirely avoids the middle-east – unlike, as is mentioned, Peter Cheyney. Philby was based in Beirut; Deighton features Beirut early in The Ipcress File (1962). Goodman explained how, in William Boyd’s Solo (2013), Bond makes his first visit to Africa. This novel also presents Bond in 1969 London, older and paunchy amid the changing, increasingly multicultural city. He waves away a copy of The Times bearing tidings of Vietnam. The Nigerian-born Boyd apes Fleming’s colonialist politics – describing a local woman’s nipples as perfectly round like coins and depicting an Africa of ‘cliché and stereotype’. This got me thinking that Solo would have been benefited by including some sort of Tiny Rowland figure – whose outrageous business ‘practices’ in Ghana have been dissected by Adam Curtis in episode 2 of The Mayfair Set (TX: 25/07/1999). Of course, for a Cameron, Johnson or Osborne, Rowland would be one of those archetypal British ‘buccaneering’ capitalists we should do everything to encourage.

Datta was asked about stereotyping; In Tintin narratives, the natives are often stereotyped – I have read Tintin in the Congo (1931), and yes, the blacks are depicted as eager, savage children in need of firm tutelage. Mentioned the natives as ‘subordinate’ to Tintin. There were fewer questions on Pamuk’s work. The general neglect of Africa was raised; it was mentioned that Graham Greene – The Heart of the Matter (1948) is set in Sierra Leone. Concerning North Africa, it was my thought that someone should write a Bond novel set during the Suez Crisis, and not straightforwardly mimic Fleming’s style…

Thursday’s literature-dominated proceedings over, relaxation began, in the non-shadowy environs of the George Inn.

[1] Porter, B. (1989) Plots and Paranoia: History of Political Espionage in Britain, 1790-1988. London: Routledge.

[2] Christie, A. (1927) The Big Four. Glasgow: William Collins & Sons.

[3] Frayling, C. (2014) The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & The Rise of Chinaphobia. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

[4] Beckett, A. (2003) Pinochet in Piccadilly: Britain and Chile’s Hidden History. London: Faber and Faber.