The final day of the conference began, with my delivering my paper on Dennis Potter’s ‘Traitor’ – downloadable here. It was not quite an easy task doing this first thing at 9.30am, after a fair few drinks the previous evening… but ample practice and the excellent conference facilities made it all a relative breeze.

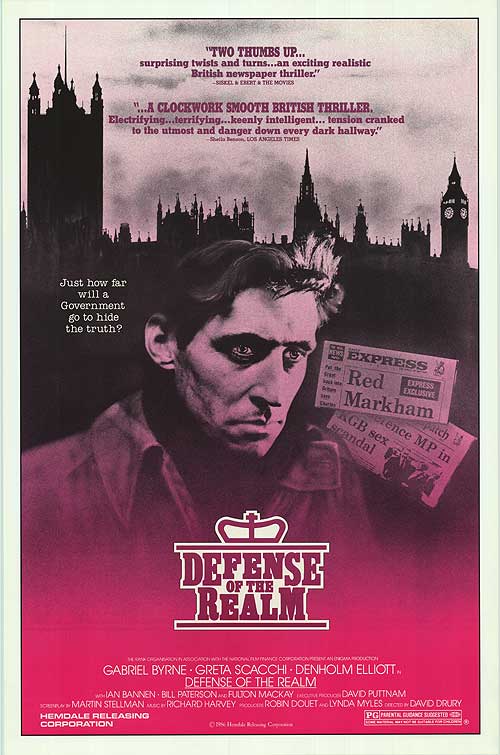

Following my 21-minute ‘oratory’, was Paul Lynch (University of Hertfordshire, GB). His paper was an especially fascinating disquisition on the British conspiracy thriller: the chief instances being 1986 films Defence of the Realm and The Whistle Blower and The Fourth Protocol (1987). Lynch’s readings were in the light of ‘LABOUR ISN’T WORKING’-‘GOTCHA’ and Thatcher, and the 1982 security scandal, with ‘mini-Watergates opening up from Westminster to Wapping’. He contextualised this is an era where CND had 110,000 members and were considered an ‘enemy within’ alongside the miners. He referred to Christopher Andrew’s 2009 history of MI5 which discussed widespread fears of Soviet infiltration in the early 1980s. The film of Defence… is considered as a sort of British Parallax View for paranoid times, starring gaunt Gabriel Byrne. His Nick Mullen takes on the establishment, with London as a metaphor and a Leviathan British state, reflecting permanency, power and defiance. The film presents ‘asinine, faceless neighbours’ and a bureaucratic machine described as ‘Kafkaesque’.

Lynch went into a discussion of The Fourth Protocol, focusing on the contesting of ideologies in production of this thriller, the novel of which was by Frederick Forsyth, whose politics were, as Lynch states, ‘to the right of Genghis Khan!’ He mentions that in Moscow there was a palpable sense that the early-mid 1980s Labour Party could be an ally, which fed into Forsyth’s right-wing paranoid vision of a Britain on the edge of left-wing revolution. The novel was adapted by George Axelrod, screenwriter who adapted key work of ‘First Cold War’ paranoia, The Manchurian Candidate, twenty-five years earlier. Lynch referred to John MacKenzie being very much on the other side of the political divide to Forsyth and the thriller writer being in despair when he watched a rough cut of the film in the editing suite, seeing how far MacKenzie had taken it from his vision. Odd considering that steadfast conservative Michael Caine had made the original suggestion to FF to film it, and had taken up a key role.

Caine also features in The Whistle Blower, which Lynch compares to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four, with its central Caine and Nigel Havers characters bearing the common-sense English name of ‘Jones’. Lynch reflected on the symbolic, evocative casting of John Gielgud and James Fox. His reading of the film is that it is in part a response to the Orwell-like dystopian measures of the Thatcher government in its mid-1980s authoritarian populist pomp. He sees te film as depicting the sacrifice of British interests to get US protection and that American influence has shattered the peace of rural Britain. It should be noted that the film was released in UK cinemas in December 1986; that January had seen the Westland crisis, which had seen conservative tensions over American dominance come to the fore.

Lynch quoted the opening from Hal Hinson’s Washington Post review of this film: ‘By now an atmosphere of subdued tension, of hushed, behind-the-hand conversations and clandestine street-corner meetings, is as indigenous to British films as Wellingtons and brollies. If the cinema is any gauge, espionage, double-agenting and secrets trading are to England what baseball is to America — a national pastime and, for some, an obsession.’ Then Michael Denning was cited regarding the influence of news stories on how we think. He posed the crucial central question regarding the impact of secret service activities on nationhood: ‘Yet what sort of society is preservable?’ This paper got me wanting to urgently watch these films, a task not yet achieved, but awaiting future holidays…!

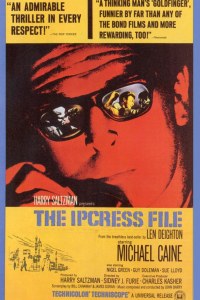

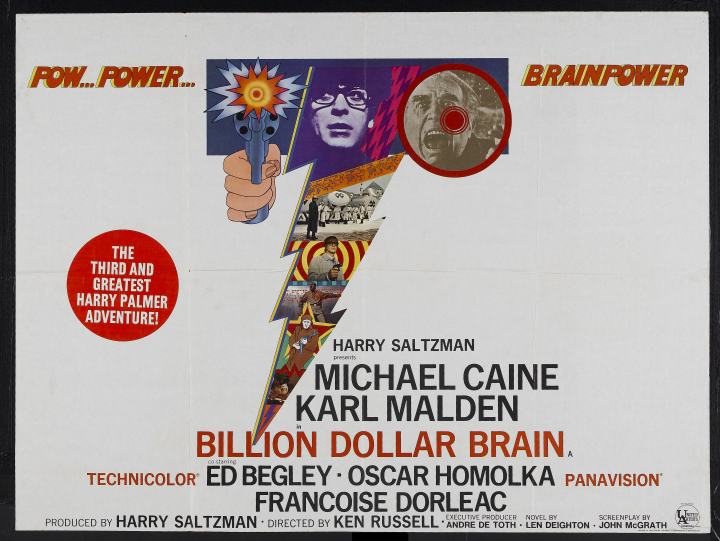

Alan Burton (Universitat Klagenfurt, AUSTRIA) opened with a question: how many in the room had seen Game, Set and Match, YTV’s 1988 adaptation of the first trilogy from Len Deighton’s triple-trilogy of novels? Of the twenty or so at least reasonably specialist folk present, only two hands went up. Burton created the sense of this series as banished to a critical oblivion, as well as obscurity. The trilogy of trilogies, featuring a new Deighton anti-hero protagonist, Bernard Samson, sold 40million books worldwide. The 13-part series was broadcast in October-December 1988, with episodes 1-5 set in Berlin, 6-10 in Mexico and 11-13 in London.

In terms of adapted Deighton, only lesser known now is Spy Story, a 1976 film directed by Canadian exploitation helmsman, Lindsay Shonteff, which Burton mentioned. Deighton was said to have wanted G, S & M to match the ‘quality’ of serial adaptations Brideshead Revisited (1981) and The Jewel in the Crown (1984). GS&M claimed a budget of £5million to be the most expensive British TV drama to date; it also boasted filming in Bolton, Lancashire, Nether Alderley, Cheshire and genuine locations like ‘Checkpoint Charlie’ in Berlin. Another curio was that star Ian Holm – second choice to Anthony Hopkins – boasted to have been in 709 of its total of 711 scenes. His performance and stamina were praised.

Otherwise, the reaction was generally dire. ‘A mess’ and ‘a disaster’, said the New York Times. Film director, novelist and critic Chris Petit in The Times criticised the bizarre casting, where ‘no-one is as one imagined them in Deighton’s novel’. Deighton himself ranted against this adaptation – ‘the tall become short; the brunettes blonde’ and bought back the rights to prevent any subsequent re-transmission. However, Burton noted its high IMDb average rating and that it could be seen as a last gasp of this sort of leisurely serial on British television, pre-1990 Broadcasting Act. He also noted plans – reported in 2013 – by Slumdog Millionaire screenwriter Simon Beaufoy in collaboration with Deighton to bring back the ‘Bond with Brains’ protagonist Samson, with a new adaptation.

This fascinating panel was rounded off by Oliver Buckton (Florida Atlantic University, USA), with one of very few conference papers focused on Graham Greene, or more specifically, Greene’s The Human Factor and its 1979 film adaptation. The novel, commenced in the 1960s, was finally finished by 1978. He had stayed at Fleming’s ‘Goldeneye’ residence, but refused to write a Bond intro. Buckton states that Greene mocks Bond through the Davis character, and that Maurice Castle’s childhood belief in a dragon is analogised to Bond, ‘in Greeneland, a figure of myth or mockery’. Buckton mentions how this novel was delayed due to the Philby affair coming out, though Castle is a ‘typical office worker’, with no resemblance to Philby. He notes the novel’s ‘unglamorous settings’ and sites it in context of the establishment’s ‘nightmare of scandal’, from Vassall to Philby to the Portland Spy Ring.

The film was adapted by Tom Stoppard; Buckton showed a clip with a very prosaic, mundane office setting – complete with the banality of Impega box-files. The shift to South African settings reflects a remove from dull routine. Buckton analyses designer Saul Bass’ opening credits, with the focus on an old-fashioned telephone line being severed; this is analogised to the film’s core relationship being hanging by a thread. It was left a moot question just how deeply this film reflected Apartheid South Africa and its relation to the Cold War.

Q&A:

Oldham started with a question for Lynch, on whether there was influence from Deighton and JLC on these conspiracy thrillers. Lynch argued that JLC was a strong influence, mentioning the reactions to the TTSS TV adaptation of 1979. Phyllis Lassner alluded to Deighton being described by thriller scholar and writer Julian Symons as a ‘poet of the genre’ and how Graham Greene downplayed the significance of his spy thrillers by describing them as mere ‘entertainments’. She then asked the panel whether these writers and John le Carré are now part of the literary canon. Buckton mentioned that, by the time of THF, Greene had given up the distinction between his ‘literary’ novels and ‘entertainments’, reflecting a clear change in critical mood. Burton mentioned that there’s often been a critical distinction: between Greene and JLC, seen by critics as having ‘credibility’ due to being involved in the secret services, and Deighton and Eric Ambler, who weren’t involved. This was memorably described as a ‘degrees of MI6-ness’ test fallen back on by critics to a perhaps problematic extent. I referred to Le Mesurier’s Adrian Harris being described by Nancy Banks-Smith in The Guardian as his ‘Hamlet’ – showing how the spy is the pivotal tortured modern figure analogous to Shakespearean heroes. As well as that Le Mesurier was viewed in the lineage of the literary and theatrical canon.

Reference could have been made to TTSS’s secure position within the TV canon, alongside I, Claudius, the aforementioned Granada adaptations of Waugh and Scott, and challenging works such as Boys from the Black Stuff (1982), Edge of Darkness (1985) and The Singing Detective (1986). No one dissent from, say, Matthew Sweet’s view that Alec Guinness’ Smiley is a great and tragic creation.[1] This canonical TV drama was to feature in the conference’s final keynote.

Lynch quoted the noted Greek-French director Costa-Gavras – “You don’t catch flies with vinegar” – saying that conspiracy films often come in for a lot of criticism as they conclude by saying: “it’s all a conspiracy; we don’t really know who to blame”. He quoted film critic John Hill on how this perception undermines these films and the depth of political comment they often make. He again quoted Hill – “A film that isn’t seen is not a film” – to explore how these films are caught between the imperative to make political points and the need to find a mainstream audience.

On this subject, I could’ve mentioned Boulting Brothers’ High Treason (1951), as an early, ‘first Cold War’ instance of the conspiracy thriller. This film is one of the clearest British examples of the ‘red plot’ narrative, with communist conspirators planning to hijack power supplies and bring the British economy to its knees. This film, insightfully analysed by Tony Shaw, was a sequel to Seven Days to Noon (1950), which I have yet to see![2]

There was a question for Buckton on the ideological dimension of the South African sequence – the character in the book not being a communist but an anti-colonialist. Buckton referred to personal loyalties being foregrounded, with Connolly not taking political sides. Anti-Bondness is there throughout Greene’s career, and his association with Philby. In the film of THF, Castle’s reasons for espionage get occluded, in comparison with the novel. There’s more focus on his relationship with Sarah and a glamorised.

Toby Manning made the point that often there’s a lack of focus on the issue of motivation. He referred to JLC’s critique of Greene’s writing a foreword for Philby’s autobiography and then that Greene wrote a sort of Philby novel without going into the political motivation. He mentioned the extreme lengths to which many go to deny communism was a genuine ideological motivation for betrayal – e.g. it’s omitted as a motive for Bill Haydon in TTSS – and asked me whether this was also glossed over in ‘Traitor’. I mentioned Raymond Williams’ review, saying that the play denies the 1930s international context, with Potter focusing on the domestic politics of unemployment and class. There was further discussion about Castle and Haydon both being anti-American rather than explicitly leftist; I commented on this issue in relation to Potter here.

I was then asked by Christa Van Raalte about the parallels between Philby and Harris in ‘Traitor’; for her, the differences stood out, with Harris being wistful, lonely and isolated, in comparison to the garrulous descriptions of Philby, post-defection. I quoted Williams again on Potter’s ‘cold, alienated method’ in showing Harris as insular and isolated, in a shabby flat in Moscow… I mentioned the key scene where he argues with the journalists about materialism in his bare flat – stating that his setting is unimportant and that they’re imposing western bourgeois value judgements on him. I concluded by that Potter ultimately isolates him in an attempt to discredit the Philby-type character. And this finished a panel that, irrespective of my own involvement, I found the most fascinating of any at the conference.

30-40 people were left by near-lunchtime on Saturday for the final speaker: Rosie White (Northumbria University, UK) gave a paper on women, ageing and espionage. This used useful initial stimuli, from Sontag’s essay on ageing as a ‘moveable doom’ to Dan Gibson cartoons, to introduce and contest the idea of older women as property of depreciating value. The ideal cover for being a spy. White spoke of the Melita Norwood case, where she was unveiled as a Soviet spy in 1999, aged 87; this was depicted in the British media as an almost Ealing comedy-esque ‘harmless eccentricity’, which may seem oddly appropriate given Matthew Sweet’s argument in Shepperton Babylon that Ealing was actually rather radical and left-wing in a lot of ways. She mentioned an interesting sounding biography and novel about Norwood.

Another long-lived old lady, Dorothy Gilman, a New Jersey, wrote 14 novels featuring Mrs Emily Pollifax, a 60-year old spy. Gilman is argued to depict this older woman figure as a disrupter of certainty; she is eccentric and unstable as well as drawing on great resourcefulness and experience. The character has featured in two adaptations: the Rosalind Russell-starring and scripted film Mrs Pollifax-Spy (1971) and, for television, The Unexpected Mrs Pollifax (1999).

White extended the thesis by analysing Connie Sachs in the TV version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy . Sachs as a human archive, ‘the memory of the Circus’, based on the real-life MI5 operative Milicent Bagot (1907-2006). Bagot had been the first person to warn MI5 about Philby’s previous membership of the Communist Party, and had also written an account of the ‘Zinoviev Letter’ scandal of 1924 that had unseated the first ever Labour government.

White showed a clip from TTSS – later acclaimed by Toby Manning as the ‘best scene ever on British television’. White analysed Reid’s roles ‘problematised typical gender roles’: eccentric performances in The Belles of St Trinian’s (1954) and The Killing of Sister George (1968) – and could surely have added the bizarre Psychomania (1973) to this litany. There was discussion of how ‘queer’ used to be associated with counterfeit: ‘queer money’, referenced as early as 1740, according to the OED. White spoke of how Sachs is all Smiley is not: she is fit, engaged and utterly vindicated by the narrative; representing a model of how we might want to age. The depiction in Smiley’s People has shifted to chair-bound, weaker and more deeply aged. White mentioned she liked the Alfredson version of TTSS, and that Kathy Burke’s Connie was more pathetic and less angry than Reid’s.

Q&A:

Judi Dench’s Q in Bond films and Nicola Walker’s Ruth in Spooks were compared, as strict head-girl types, and are later placed in the context of Stella Rimington, DG of MI5 from 1992-96.

There was mention of cultural pressures to ‘keep young’ and the disturbing sense that pensions are being reduced and downgraded. There was a reference to how no-one has done ‘Old Bond’, which got me thinking about the melancholy, slow-burning Play for Today: ‘The General’s Day’ (1972), with Alastair Sim as its fading old reprobate of a titular protagonist. This tallied with a later comment: ‘not to be sexual in the twentieth century is a bit queer’. If women married, they would be stricken from the BBC and the British secret service. Gender re-appropriations include Salt (2010) with a married woman protagonist, and Ed Brubaker’s comic series, Velvet (2013- ), with Bond reimagined as a female secretary.

Questioning led to a return to James Chapman’s concern with The Lady Vanishes: Miss Foy being more than just a ‘little old lady’. There was mention of strong elder character in The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) – Marjorie Fielding? – and I inevitably also thought of the remarkable Katie Johnson performance in that vital British film The Lady Killers (1955). White pertinently mentioned a Guardian article by Lucy Mangan published on the day before this conference started: ‘Whatever happened to the Great British Battleaxe?’ wherein Mangan elaborated upon Alan Bennett’s recent comments bemoaning the cultural loss of this archetype.

The concluding remarks were brief and warm; there was a giveaway of Charles Cumming’s novel A Foreign Country; Manning not being especially complimentary about the writer, when comparing him with John le Carré! There was much talk of doing another such conference in 2016, which would be a fine prospect.

List of literary, film and television works referred to in the conference talks I attended:

LITERATURE: FICTION

Akunin, Boris – The Turkish Gambit (1998)

Boyd, William – Restless (2006)

Boyd, William – Solo (2013)

Bridge, Ann – A Place to Stand (1953)

Brubaker, Ed – Velvet (2013- )

Buchan, John – The Powerhouse (1916 – written 1913)

Buchan, John – The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915)

le Carré, John – The Russia House (1989)

le Carré, John – The Spy who came in from the cold (1963)

Childers, Erskine – The Riddle of the Sands (1903)

Conrad, Joseph – The Secret Agent (1907)

Cumming, Charles – A Foreign Country (2012)

Cumming, Charles – A Spy by Nature (2001)

Deighton, Len – The Ipcress File (1962)

Fleming, Ian – Casino Royale (1953)

Fleming, Ian – Dr No (1958)

Fleming, Ian – Goldfinger (1959)

Gilman, Dorothy – The Unexpected Mrs. Pollifax (1966)

Greene, Graham – The Heart of the Matter (1948)

Greene, Graham – The Human Factor (1978)

Greene, Graham – Our Man in Havana (1958)

Herge – The Adventures of Tintin: Red Rackham’s Treasure (1943)

Herge – The Adventures of Tintin: Prisoners of the Sun (1946-48)

Herge – The Adventures of Tintin: The Seven Crystal Balls (1946-48)

Kipling, Rudyard – Kim (1900-01)

MacInnes, Helen – Above Suspicion (1941)

Maugham, W. Somerset – Ashenden (1928)

Moore, Alan – The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999- )

Oppenheim, E. Phillips – Miss Brown of X. Y. O. (1927)

Pamuk, Orhan – The New Life (1997)

Pamuk, Orhan – My Name is Red (2001)

Pamuk, Orhan – The Black Book (1994)

Pynchon, Thomas – The Crying of Lot 49 (1966)

Pynchon, Thomas – Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

Ray, Satyajit – Feluda: A Bagful of Mystery

Ray, Satyajit – Feluda: The Criminals of Kailash

Rooney, Jennie – Red Joan (2013)

Schreyer, Wolfgang – Die Suche oder Die Abenteuer des Uwe Reuss (The Search) (1981)

Stoppard, Tom – Hapgood (1988)

Stoppard, Tom – Jumpers (1972)

Thürk, Harry – Der Gaukler (1978)

LITERATURE: NON-FICTION

Andrew, Christopher (2009) The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5

Arendt, Hannah (1958) The Human Condition

Baker, Brian (2012) ‘”You’re quite a gourmet, aren’t you, Palmer?” : masculinity and food in the spy fiction of Len Deighton’, Yearbook of English Studies, July, 42, pp.30-48

Burke, David (2009) The Spy Who Came In From the Co-op: Melita Norwood and the Ending of Cold War Espionage

Burton, Alan (2016) Historical Dictionary of British Spy Fiction

Chapman, James (2007) Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films

Denning, Michael (1987) Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller

Greene, Graham (1980) Ways of Escape

Haffner, Sebastian (2000) Defying Hitler: A Memoir (*written 1940)

Halberstam, Judith (2011) The Queer Art of Failure

Hinson, Hal (1987) ‘The Whistleblower (PG)’, The Washington Post, 19th August [online] [accessed: 29/11/15]

Lanza, Joseph (2007) Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films

Mangan, Lucy (2015) ‘Whatever happened to the Great British Battleaxe’, The Guardian, 2nd September [online] http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/02/battleaxe-alan-bennett-matriarch-extinction [accessed: 29/11/15]

Moran, Christopher (2013) ‘Ian Fleming and the Public Profile of the CIA’, Journal of Cold War Studies, (15)1, p.119-46 (Winter)

Said, Edward W. (2000) – ‘Introduction’ to Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, Penguin Classics

Sellers, Robert (2008) The Battle for Bond: second edition

Sontag, Susan (1972) ‘The double standard of ageing’, Saturday Review, 23rd March

White, Rosie (2007) Violent Femmes: Women as Spies in Popular Culture , Routledge

FILM

Above Suspicion (dir. Richard Thorpe, USA, 1943)

The Belles of St. Trinian’s (dir. Frank Lauder, GB, 1954)

The Boston Strangler (dir. Richard Fleischer, USA, 1968)

A Bullet for Joey (dir. Lewis Allen, USA, 1955)

Casablanca (dir. Michael Curtiz, USA, 1942)

The Conspirators (dir. Jean Negulesco, USA, 1944)

The Defence of the Realm (dir. David Drury, GB, 1986)

Dr Goldfoot and the Girlbombs (dir. Mario Bava, ITA/USA, 1966)

Don’t Raise the Bridge, Lower the River (dir. Jerry Paris, GB, 1968)

Double Indemnity (dir. Billy Wilder, USA, 1944)

Flight to Hong Kong (dir. Joseph M. Newman, USA, 1956)

Foreign Correspondent (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1940)

Four Flies on Velvet (dir. Dario Argento, 1971

The Fourth Protocol (dir. John MacKenzie, GB, 1987)

Goldginger (dir. Giorgio Simonelli , ITA/SPA, 1965)

La Guerra Segreta, aka. The Dirty Game (dir. Christian-Jaque, Werner Kilinger, Carlo Lizzani & Terence Young, FRA/ITA/WGER/USA, 1965)

The House on 92nd Street (dir. Henry Hathaway, USA, 1945)

The Human Factor (dir. Otto Preminger, GB, 1979)

I Deal in Danger (dir. Walter Grauman, USA, 1966)

I Was a Spy (dir. Victor Saville, GB, 1933)

International Lady (dir. Tim Whelan, USA, 1941)

The Iron Curtain (dir. William A. Wellman, USA, 1948)

The Killing of Sister George (dir. Robert Aldrich, USA, 1968)

The Lady Has Plans (dir. Sidney Lanfield, USA, 1942)

The Lady Vanishes (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, GB, 1938)

The Lavender Hill Mob (dir. Charles Crichton, GB, 1951)

The Leather Boys (dir. Sidney J. Furie, GB, 1964)

Liberation (dir. Yuri Ozerov, SOV.U/EGER/YUG/ITA/POL, 1970-1)

Lisbon (dir. Ray Milland, USA, 1956)

A Man Could Get Killed (dir. Ronald Neame & Cliff Owen, USA, 1966)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, GB, 1934)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1956)

Le mépris, aka. Contempt (dir. Jean-Luc Godard, FRA/ITA, 1963)

Mission Bloody Mary (dir. Sergio Grieco, ITA/SPA/FRA, 1965)

Mrs Pollifax-Spy (dir. Leslie H. Martinson, USA, 1971)

Modesty Blaise (dir. Joseph Losey, GB, 1966)

Night Train to Munich (dir. Carol Reed, GB, 1940)

North by Northwest (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1959)

Notorious (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1946)

Operation Kid Brother, aka. O.K. Connery (dir. Alberto Di Martino, ITA, 1967)

One Night in Lisbon (dir. Edward H. Griffith, USA, 1941)

A 008, operazione Sterminio (dir. Umberto Lenzi, ITA/EGY, 1965)

‘The Palace of a Thousand Lies’ (1941 – scenario)

The Parallax View (dir. Alan J. Pakula, USA, 1974)

Pickup on South Street (dir. Samuel Fuller, USA, 1953)

Psychomania (dir.

Rome Express (dir. Walter Forde, GB, 1932)

Sabotage (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, GB, 1936)

Saboteur (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1942)

Salt (dir. Philip Noyce, USA, 2010)

Secret Agent (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, GB, 1936)

Secret Agent Fireball, aka. The Spy Killers (dir. Luciano Martino, ITA/FRA, 1965)

Skyfall (dir. Sam Mendes, GB/USA, 2012)

The Snake Woman (dir. Sidney J. Furie, GB, 1961)

The Spy in Black (dir. Michael Powell, GB, 1939)

Spy Story (dir. Lindsay Shonteff, GB, 1976)

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (dir. Martin Ritt, GB, 1965)

Superseven chiama Cairo (dir. Umberto Lenzi, ITA/FRA, 1965)

36 Hours (dir. George Seaton, USA, 1964)

The Secret Door (dir. Gilbert Kay, USA/GB, 1964)

State Secret (dir. Sidney Gilliat, GB, 1950)

The Thirty-Nine Steps (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, GB, 1935)

The Thomas Crown Affair (dir. Norman Jewison, USA, 1968)

Topaz (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1969)

Torn Curtain (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1966)

The W Plan (dir. Victor Saville, GB, 1930)

The Whistle Blower (dir. Simon Langton, GB, 1986)

Wonderful Life (dir. Sidney J. Furie, GB, 1964)

The Young Ones (dir. Sidney J. Furie, GB, 1961)

TV

The Americans (USA, FX, 2013- )

Brideshead Revisited (GB, Granada, 1981)

Callan (GB, ABC/Thames, 1967-72)

Game, Set and Match(GB, YTV, 1988)

Homeland (USA, Showtime, 2011- )

Indian Summers (GB, C4, 2015- )

The Jewel in the Crown (GB, Granada, 1984)

The Sandbaggers (GB, YTV, 1978-80)

Smiley’s People (GB, BBC, 1982)

Spooks (GB, BBC-1, 2002-11)

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (GB, BBC, 1979)

The Unexpected Mrs Pollifax (USA, CBS, 1999)

Das unsichtbare Visier (GDR, 1973-79)

[1] Sweet, M. (2005) Shepperton Babylon: The Lost Worlds of British Cinema. London: Faber and Faber, pp.185-8

[2] Shaw, T. (2006) British Cinema and the Cold War: The State, Propaganda and Consensus. London: I.B. Tauris, pp.40-5